Module 3: Role of guidance in mobility

| Site: | Euroguidance Latvia Academy |

| Course: | Resource library on mobility guidance |

| Book: | Module 3: Role of guidance in mobility |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Thursday, 5 February 2026, 7:15 PM |

Description

EXPECTED LEARNING OUTCOME: You will know how to support clients before, during and after a learning mobility period and develop your own personal toolbox

1. Guidance practitioners' roles in mobility

Support from a guidance practitioner can make a huge difference for a successful mobility period for the client. It can also contribute to broadening the participation in mobility. According to Danish mobility expert Søren Kristensen, the guidance process in relation to mobility can be divided into three main phases: before mobility, during mobility and after the student returns home.

1.1. Before mobility

Proactive or reactive counsellors

Often the guidance work prior to a stay abroad is mostly reactive; the guidance counsellor answers questions regarding options and opportunities from the applicants who made contact on their own initiative or from applicants who participate in a project. This approach may lead to studying abroad becoming an activity only for resourceful people who already have taken the initiative or have the perspective and the courage to take the step.

Studies show that also less resourceful people can benefit from a stay abroad, if it is well organised and well implemented and fits into the applicants’ profiles. It is generally a challenge for guidance practitioners to work more proactively with stays abroad; encouraging and motivating people to include a period abroad in the framework of their education, even if they may not have initially considered the idea or do not feel comfortable with such a choice.

- Motivate. Other people's stories can often be the first spark for interest of a stay abroad. It does not necessarily have to be the well-formulated and successful storytellers; it is more important that the listener is able to identify with the teller and get a feeling of "I could do that too". If it is not possible to invite people to talk about their experiences from studies a or training abroad or the students can listen to recorded stories or read an interview. Showing a video is also a good way to inspire or start a conversation. Here are a few examples:

- Hilda from Sweden studied in Ireland. Now she works in the municipality with climate related tasks:

- Sofia from Sweden went on an exchange to South Africa and is now working as a nurse:

- Clarify. The individual's own attitude to the stay abroad is crucial for a good experience. Here, the mobility guidance work can focus on determining the individual’s readiness to face the world. Will this student be able to handle this type of international exchange? The mobility guidance work can also contribute to a clear picture of how the stay abroad fits into the individual's future plans, so that the exchange does not become an isolated phenomenon, without connection to planned studies or work.

- Prepare.

- Linguistic preparation. Language skills increase security and facilitate a deeper understanding. Language is also a key to becoming part of a social context. But there is no general advice for linguistic preparation as these depend on the individual's prior knowledge. The Council of Europe (COE) has developed a model for describing skills in foreign languages. That model (see below) can be used for a self-assessment that can form the basis for an educational plan for language learning before and during a stay abroad. → Overview of the different levels in the Council of Europe's reference framework for languages, from A1 to C2 (link opens website in new tab) https://sv.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gemensam_europeisk_referensram_f%C3%B6r_spr%C3%A5. Linguistic preparation can be about practicing a language you already know by reading, watching movies, etc. It can also be a good idea to produce or hand out glossaries or wordlists that the participant can learn before the stay and use in everyday life. In addition, language preparation can be about doing language tests to show eligibility for various educations

- Educational preparation. From a learning point of view, one can see several possible goals with a stay abroad. It may, for example, be about developing international competences (knowledge of foreign languages and intercultural qualifications). The focus can also be subject-specific, study-related or professionally oriented knowledge. Personal development might also be a goal, gaining the ability to handle differences and an ability to change.

- Individual curriculum. An exchange or a volunteer experience can include guided learning reflection, but most often it is up to the person traveling to try to gather his or her thoughts i.e., "learning by doing". Increased personal responsibility for one's own learning characterises most stays abroad. Regardless of what stay abroad entails, an individual curriculum facilitates both follow-up and reflection afterwards. Here learning objectives for personal development can be included.

- Mental and cultural preparation. Those who are mentally prepared for the fact that staying in another country can include unexpected situations and attitudes, have greater opportunities to meet various challenges. Some of them are general to everyone who travels and it can be good to point out that e.g. homesickness and doubts disturb most people at times.

- Do cultural research. Cultural preparation can make the difference between a successful stay and a period of difficulties and disappointment. Therefore, encourage the participants to learn as much as possible about the culture that awaits them. Films, music and local fiction can be very useful. It also helps to imagine what it would mean to live in a different culture and under different living conditions. How to greet someone? Is it okay to talk about politics? What to do with the toilet paper? The more the participant knows before departure, the easier it will be. Important information and personal reflections are most easily obtained via the internet and social media.

- Our perspective is not the only one. No matter how much you read about the country in advance, it is difficult to comprehend everything new, the fine print, what is usually called culture. What do people really mean when they say something? What lies between the lines? The participants see and understand the new country from their own cultural pre-understanding, in the same way as the people in the host country walk around with their cultural perspective.

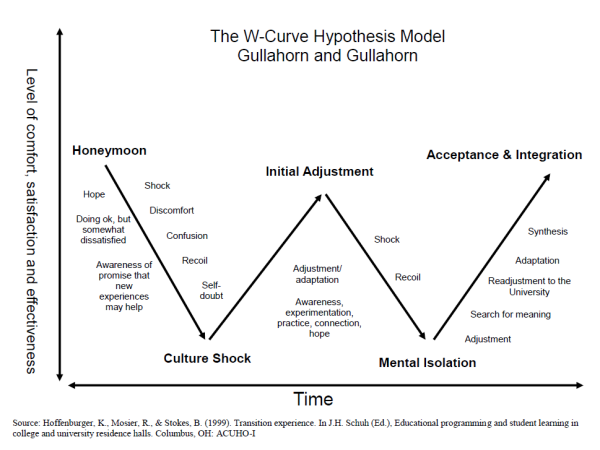

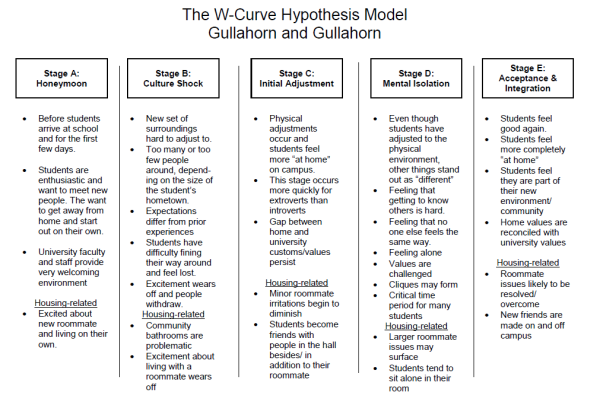

W-curve

The W-curve is a model describing emotional and cognitive reactions to intercultural experience. At first, everything is exciting and one is boosted with positive energy. Then, the person might start to experience difficult emotions like discomfort and confusion. At this stage, depending on the age, homesickness, and thoughts about returning home are prevalent. Then, if the student prevails, a new sense of adaptation and hope occurs. Again, after a while, the student may experience another mental stress situation (mental isolation). Deep learning and intercultural awareness are the next steps where the student re-examines and readjust to the new context.

As a counsellor, you can talk about the W-curve and the possible stages that the person is likely to encounter. Looking at the W-curve once again when the student returns and discussing the experiences, may also deepen the learning process.

The W graphs

Guidance counsellors should also prepare the pupil or the student going abroad with the “re-entry worm”. This is a reversed W-curve; however, it has another shape. Again, the joy of seeing friends and family again (“the honeymoon phase”) overshadows some difficulties. Then, something might feel different, and the student may presume a critical stand against what was formerly taken for granted. And especially the friends’ loose interest in the stories from the stay abroad. At this stage, the “re-entry worm” may need some assistance to overcome the negative spiral and help the student reflect on the meaning of difference and feelings from the reversed culture-shock into balanced re-adaptation.

**

Watch a Danish video about challenges of mobility stays:

**

1.2. During mobility

The guidance counsellor usually has a limited role to play during the stay abroad. However, pedagogical, social and psychological aspects of the stay may still need attention in this phase.

The guidance counsellor usually has a limited role to play during the stay abroad. However, pedagogical, social and psychological aspects of the stay may still need attention in this phase.

- Support in the learning process. The participant must take greater responsibility for their own learning during a stay abroad and may therefore need support in the learning process. Learning takes place when the participant transforms their educational and social experiences into experiences that are used in everyday life. A continuous reflection can facilitate the process. For example, you can ask the participant to document what is happening by keeping a travel diary. An important part of the learning process requires the participant to have a high a degree of contact with the community in the host country. This presupposes proper preparation and a readiness to help with the introduction into the host country. In this regard, it matters whether the participant travels alone or in a group.

- Mentorship. The exact function of the mentorship depends on the needs of the specific participant. A study period in another country is a kind of problem-based learning - the participants are given the opportunity to find their own solutions to new and different problems. It promotes personal development. However, the uncertainty and discomfort must not exceed what the participant can handle. At the same time, the participant must not be overprotected. The participant needs to own his or her personal and professional development.

- Prepared for crisis. Being prepared for a possible crisis and having a clear responsibility for the practical and social aspects during a stay are necessary to be able to identify problems that participants cannot solve on their own. The mentor role should also include a psychological dimension with a readiness to handle crises. The key is to be able to refer the participant to the right authority in the event of illness, depression and similar crises. In a crisis, it may also be necessary to coordinate the efforts with other representatives at home and in the host country in order to determine the causes of the problem and make decisions about who should do what. The problems may also relate to homesickness or a desire to cancel a stay abroad prematurely, which can make a participant feel overwhelmed. Whether the problems relate to studies, employment or internship do not matter: There should always be a contact person to turn to discuss current situations.

**

Watch a Danish video about everyday life abroad:

**

1.3. After the student returns home

The learning process does not end when the participant returns to their home country. The goals set prior to the stay abroad must be evaluated and it is crucial to gather and report the acquired knowledge and skills to decide in which way they should be credited. As a guidance counsellor, you can help optimise the learning outcome of the stay abroad through discussions and evaluations. The learning process that began in connection to the stay abroad needs to be facilitated through a frame and direction. How can the participant benefit from the new experiences, competencies and skills in a career and educational contexts?

The learning process does not end when the participant returns to their home country. The goals set prior to the stay abroad must be evaluated and it is crucial to gather and report the acquired knowledge and skills to decide in which way they should be credited. As a guidance counsellor, you can help optimise the learning outcome of the stay abroad through discussions and evaluations. The learning process that began in connection to the stay abroad needs to be facilitated through a frame and direction. How can the participant benefit from the new experiences, competencies and skills in a career and educational contexts?

- Recognition of formal competencies. Naturally, most people want to include what they achieved during their stay abroad in their CV and, in the vast majority of cases, studies and work abroad constitute a merit in itself. Many participants also think that these learning outcomes and qualifications describe themselves and do not apply for an evaluation of their competencies in their home country afterwards

- Start from the education plan. If a plan or goal was articulated before the stay abroad, it may work as the starting point for an evaluation. Evaluating the plan or goal is important for recognizing qualifications as part of a formal training, and for the participant's own confirmation and reflection of what has happened and what skills he or she has acquired. Anyone who has participated in an exchange program at a university can in most cases get credits for their study time abroad. However, if the student went abroad as a free mover (a student enrolled outside any regular or standard program) it is not always obvious how to credit the merits or qualifications. Good documentation of qualifications is essential here. If a student has participated in a school project that included exchange programs with other countries, the exchange program is usually an integrated part of the study course. For example, in vocational programs they may go abroad for an internship.

- Process the experience. This stage in the mobility guidance process is perhaps the most difficult, partly because the effects may be subtle or not immediately apparent, and partly because a processing or summary is often not requested.

- Non-formal learning and personal development. Since many of the competencies associated with personal development are usually informal and more general, they do not belong to any specific subject area. This means that schools or universities may not feel responsibility for evaluating this dimension of a stay abroad. Instead, formal learning connected to specific subject areas is usually in focus. Informal learning includes the challenges and the daily hassle that are often a large part of a stay abroad and that contribute to the development of the young individual. These skills can be important to include in a CV or talk about at a job interview, but they are skills that the student may need support to discover and put into words.

- Putting perspective on the experiences is about working with the thoughts that the participant has had during their stay abroad, which is part of the intercultural learning process. These may be issues and/or experiences that have remained unexplained or for which the participant himself has found an explanation. Therefore, it is a good idea to discuss the stay abroad with the participant after returning home, with these issues or experiences as a starting point, and to try to get a perspective on them together (both positive and negative). The starting point is broad questions such as "What do you think of Germany, now that you have been there for three months?", "Was there anything that surprised you?", "Which aspects of the work / studies differed the most from what you know from home?” and so on. These types of questions lead to areas that can be further discussed.

- Problematise and challenge generalising explanations. A guidance counsellor who has personal and in-depth knowledge of the country and the culture in which the participant has lived can of course use that knowledge in the discussion. In the vast majority of cases, however, it is the participant who is the "expert" - it is (s)he who has had a direct contact with the country. The role of the guidance counsellor is thus to problematise and challenge and try to find other explanatory models for what has happened. It is not about finding the "right" explanations, but just about initiating a reflective process

As a guidance practitioner, you have many ways of making the client engage in reflection processes. These techniques might be a start:

- Exceptions: Examples of episodes where things worked out or did not work out. What did the person do or say? What could have been the alternative? What was the significant element?

- Coping: Make the student explain their coping strategies

- Progress: When did things start to get better? And why?

- Scaling: How satisfied are you with your efforts (examples)? Why do you rate yourself like this?

The guidance process after the mobility period includes guidance on what to take on board, what steps to take next and how to use the new competences in the future.

Preserve the positive

In the same way that the participant needs to prepare mentally and culturally for a stay abroad, one needs to understand that it is a small adjustment to come home again. Upon returning home, the participant (consciously or unconsciously) is put under pressure by his or her surroundings to become the person he or she was before departure. Provided that the changes that have taken place are positive, support may be needed for the “new” personality and help to preserve the change. This can be done by supporting the participant to put the changes into words and help in drawing any educational and career conclusions from them.

After a transformative stay abroad, it might be tricky to create a "bridge" between experiences and skills. Many exchange students want to talk about what they have done but expressing these experiences in terms of skills or abilities has proved difficult. Here the ELD (Experience, Learn, Describe) competency list may be of help. The words marked with a globe are skills that most often are connected to a stay abroad. More information about the ELD method can be found here: eldkompetens.se

**

2. How can the quality of the mobility process be improved?

There is an increased emphasis on increasing not only the number of mobilities abroad but also their quality. The costs related to each mobility are high, both for the individual and the society, since mobility grants are paid for by the taxpayers. It is therefore important that both the individual and society get some real value for their time and money.

There is an increased emphasis on increasing not only the number of mobilities abroad but also their quality. The costs related to each mobility are high, both for the individual and the society, since mobility grants are paid for by the taxpayers. It is therefore important that both the individual and society get some real value for their time and money.

2.1. For the individual

The benefits of undertaking learning mobility go beyond intercultural awareness and can include development of personal competences, active citizenship and employability of participants. A policy paper from the European Commission explains:

“Learning mobility, meaning transnational mobility for the purpose of acquiring new knowledge, skills and competences, is one of the fundamental ways in which young people can strengthen their future employability, as well as their intercultural awareness, personal development, creativity and active citizenship. Europeans who are mobile as young learners are more likely to be mobile as workers later in life” (Council of the European Union 2011).

Even though success rates of mobility programmes are often described in terms of numbers of participants involved, this approach does not provide a quality perspective. For quality, what is important is the nature and extent of what knowledge, skills, values and attitudes individuals bring home, and how these acquisitions contribute to the development of communities, societies and the individuals themselves (European Commission, 2017). Various evaluations and research show that good quality learning mobility can indeed bring about quality outcomes.

Mobility guidance, described in the previous sections, brings quality to the mobility process through the support offered to the individual in the different phases of mobility. Guidance counsellors who are aware of and believe in the added value of mobility for the individual, have the potential to make use of mobility as a tool to strengthen individuals and develop their skills and competences. In the global world of today, it is more important than ever to offer young people good opportunities for developing their ability to see themselves in an international context and to make international comparisons and reflections.**

2.2. For society

Research on mobility tends to focus on the benefit to the individual whereas research on the benefits to the society at large is difficult to find. However, the research that exists, reveals how individuals who study abroad benefit their native society when they return. By bringing with them a global perspective, they help foster the spirit of cross-national cooperation and the opening up of entrepreneurship and innovation.

Research on mobility tends to focus on the benefit to the individual whereas research on the benefits to the society at large is difficult to find. However, the research that exists, reveals how individuals who study abroad benefit their native society when they return. By bringing with them a global perspective, they help foster the spirit of cross-national cooperation and the opening up of entrepreneurship and innovation.

According to research, the socioeconomic status of those who participate in mobility activities is higher than of those who do not participate. Research also shows that those who participate in mobility activities and have a lower socioeconomic status benefit more than those with a higher socioeconomic status.

**

2.3. Valuable tools for support

There are tools and materials on international mobility available to support the work of guidance practitioners. By utilising these tools, you, as a guidance practitioner, can inspire your clients, present the different opportunities for mobility and tell them about the importance of international competences.

There are tools and materials on international mobility available to support the work of guidance practitioners. By utilising these tools, you, as a guidance practitioner, can inspire your clients, present the different opportunities for mobility and tell them about the importance of international competences.

The Europass portal

In the Europass portal, students contemplating mobility, can create a profile in 29 languages and use it when writing their application. They can then use the profile to make a CV which demonstrates not only their working experience and previous education but also social skills, digital knowledge and the knowledge of different languages. Link to the Europass portal in English (you can change the language in the top right corner). Link to a CV tutorial.

The European Qualification Framework

The EU developed the European Qualifications Framework (EQF) as a translation tool to make national qualifications easier to understand and more comparable. The framework consists of 8 levels and each country participating in the initiative has subsequently placed its own education to a level, numbering from 7 to 12. At present, all the EU countries and 11 other countries have referenced their education to a level. A few countries are still in the process of doing so. This process makes it much easier for students to get recognition for their studies in other European countries. Further information.

Study in …

Through the Euroguidance website, it is possible to look up the "study in …" webpages for all European countries. These pages provide information in English about study possibilities in each country and practical advice for students considering living there.

Private resources

There are also privately owned resources, such as bachelorsportal.com and mastersportal.com, which display information submitted by education institutions worldwide that wish to be advertised. Therefore, the list of opportunities in these private resources will not be exhaustive but does present a selection of learning opportunities aimed at international students.

Examples of good practice

Maailmalle.net a Finnish website targeted at young people who are looking for international mobility opportunities. Maailmalle.net is also an information and guidance tool: guidance practitioners can use the website when discussing the possibilities of going abroad for studying, training and volunteering with their clients.

3. MODULE 3: KEY POINTS TO REMEMBER

Guidance practitioners' roles in mobility

- It can be challenging for counsellors to take a pro-active role in motivating less resourceful students. However, this broadens access to mobility and it is a way to help students grow.

- Types of pre-mobililty preparation include linguistic, educational, curricular, mental, and cultural.

- The W-curve is a model that describes the emotional and cognitive reactions to an intercultural experience and can be used for guiding the student both before and after the mobility.

- The "re-entry worm" is another model that can be used in counselling both before and after the mobility period. This is a reversed W-curve aimed at preparing the student for the reversed culture-shock when returning home.

- When abroad, the mobility participants have to take greater responsibility for their own learning and may therefore also need support for their learning process, through some follow-up measures.

- The guidance process after the mobility period includes guidance on what to take on board, what steps to take next and how to use the new competences in the future.

How can the quality of the mobility process be improved?

- The benefits of undertaking learning mobility go beyond intercultural awareness and can include development of personal competences, active citizenship and employability of participants.

- Guidance counsellors who are aware of and believe in the added value of mobility for the individual, have the potential to make use of mobility as a tool to strengthen individuals and develop their skills and competences.

Valuable tools for support

- In the Europass portal, students contemplating mobility, can create a profile in 29 languages and use it when writing their application.

- The European Qualifications Framework (EQF) is a translation tool to make national qualifications easier to understand and more comparable.

- Through the Euroguidance website, it is possible to look up the "study in …" webpages for all European countries.

- There are also privately owned resources, such as bachelorsportal.com and mastersportal.com, which display information submitted by education institutions worldwide that wish to be advertised.